by Cora Angier Sowa

Duke Ellington at New York University

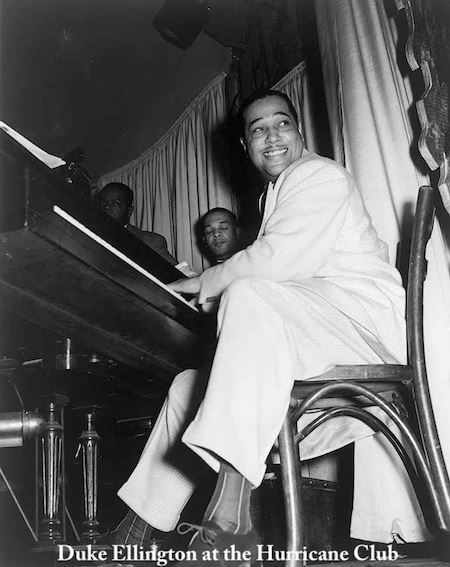

In 1932, Percy Grainger was teaching a course called "A General Study of the Manifold Nature of Music" at New York University. On October 25, he invited the famous jazz bandleader Duke Ellington and his orchestra to perform several compositions for his class. Under such bandleaders as Ellington (pictured above), jazz had been adapted from different kinds of African and African-American song and made into forms that were popular with a wider, i.e. white, audience. Grainger had become a big fan of jazz, which he saw (as might be expected of him) through the lens of his own rather peculiar musical views.

The origins of jazz

The beginnings of jazz are usually associated with New Orleans, with its brass bands marching in Mardi Gras parades and jazz funerals, and with the singing and dancing in Congo Square, a neighborhood just north of the French Quarter, where enslaved Africans, given the day off on Sunday, would set up a market (at which they could often make enough money to buy their freedom) and dance to rhythms and songs inherited from Africa, like the Bamboula, Calinda, and Juba. The area is now included within Louis Armstrong Park.

But the origins of jazz are complicated, drawing from many sources, African, Asian, and European. In Africa, the roots go back to the songs of the griots or bards, who were the keepers of the history of the tribe, to songs to accompany work, songs for religious ceremonies, and songs of play. Percy Grainger's friend Natalie Curtis recorded many of these songs, and her work in collecting the songs of African and African-American singers was discussed in a previous blog, Natalie Curtis, Busoni, and Grainger.

Songs of the gandy dancers

In America, the African slaves continued the traditions of song, often improvising words to fit the circumstances. There were songs for cotton-picking (sometimes with acid remarks about the white boss when he was out of earshot). With the end of slavery, African American laborers continued the tradition of improvising songs or chants to accompany their work, on the railroad or in construction.

In America, the African slaves continued the traditions of song, often improvising words to fit the circumstances. There were songs for cotton-picking (sometimes with acid remarks about the white boss when he was out of earshot). With the end of slavery, African American laborers continued the tradition of improvising songs or chants to accompany their work, on the railroad or in construction.

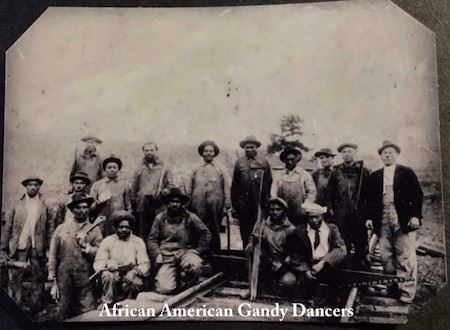

The "gandy dancers" were the track workers on the railroads, in the days before mechanical cranes and steam shovels, like the men pictured in the tintype shown above. (We notice the plump white supervisor standing on the right of the picture.) In the North, the gandy dancers were generally white, many Irish or German. In the South, they were usually Black. Even after the track was laid, crews would periodically have to straighten the track, shoved out of alignment by the constant passing of the heavy trains above. A long line of men with crowbars would stand on one side of the rail, using brute force to rhythmically heave it into place, moving in unison. Spiking the rails in place also required teamwork. It was generally a two-man job, with one man on each side of the rail, striking the spike in fast alternating strokes. The work of the gandy dancers was accompanied by songs or chants, like the sea shanties of sailors. These served two functions, to help keep the rhythm of the work, and to motivate the workers. These chants usually followed a call-and-response pattern, which we find as an important component of jazz. One member of the crew, the "caller," chants a verse of some kind, answered by the others as they heave the rail, thus, giving a heave at each "huh":

Up and down this road I go

Skippin' and dodging a 44

Hey man won't you line 'um...huh

Hey won't you line 'um...huh

Hey won't you line 'um...huh

Hey won't you line 'um...huh

The caller might choose different topics for the initial verse, turning to sexual jokes if the men were tired and needed encouragement (but these latter only when they were out of earshot of women and children and of the white railroad owners).

An example of improvisation

Improvisation to fit the circumstances was an important part of these songs, as it would be for jazz. My own father, Robert M. Angier, describes two examples from Black crews he witnessed when on a summer job with his father's civil engineering firm early in the twentieth century. He recorded them in his book Why Poetry, in the chapter called "Marching Songs."

"... I recall a crew, in Memphis, Tennessee, who worked as a team putting together the forms for the reinforced concrete piling (which I was there to inspect) at the successive commands which, although not verse, rolled rhythmically from the lips of the gang boss. It went something like this:

"Pick up de one side:

Set in de cage:

Pick up t'othah side:

Stick in the pins:

Shake 'im!

"Ain't got but one eye!" piped a youth.

"Whut ain't got but one eye?" intoned the boss.

"Dis hyeah fawm! [form]" answered the youth. One of the lugs on the edge of the half-octagonal steel sheet had broken off, so that the linking strip could not be fastened. With a brief glance in my direction, the gang boss chanted:

"Git a wy-ah!"[wire]

One of the men produced a length of wire which, when looped around the remaining opposite lug and passed under the form, shaped a temporary eyelet for the other side, while all the other men stood at attention until, the loop made and the pin run through, the final command was given:

"Cah-yeh it 'way!"

Another group, working on "double tracking" and elevating roadbed along the Des Plaines River, near Chicago, included one fellow who, I heard him tell the foreman, wanted to "go back to Bobo, Mississippi. B-o-b-o," he spelled it out carefully, in case the foreman might not know. And later I heard him cogitating vocally, to the rhythm of spike maul or tamping bar:

"Ah won-dah of a soot-case'll hol mah clo's!"

"Matchbox'll hol' yuah clo's!" jibed another, and, with perfect calm, without missing a beat, the first continued his improvised chant, but changed the "lyric" (!) to read:

"Ah won-dah of a match-box'll hol' mah clo's!"

Fusion of African and European music traditions

In America, African traditions of complicated, syncopated rhythms, call and response, improvisation, and rhythmic chanting rather than European-style melodic development and orchestration were fused with European musical traditions in many ways. As African slaves adopted Christianity, forms of gospel music and spirituals came into being. In popular entertainment, ragtime fused syncopated polyrhythms with the band music popularized by John Philip Sousa. Ragtime was played on pianos by "professors" in "sporting houses" (bordellos) in the Storyville section of New Orleans. ("Storyville" was the popular name given to a red-light district defined by legislation proposed by City Councilman Sidney Story, to the councilman's embarrassment.)

Ragtime, particularly associated with the "King of Ragtime" Scott Joplin (composer of the "Maple Leaf Rag," among many other pieces), was the first African-American music to have an impact on the wider American and European public. It was popularized in polite mainstream culture by its playing by "society" dance bands. Ragtime even influenced such classical composers as Erik Satie, Claude Debussy, and Igor Stravinsky. Percy Grainger's first exposure to jazz was the ragtime that he heard in the music halls of London.

Spanish, Afro-Cuban, and Creole influences also made their way into the development of African American music.

The "Swing Era" and the big band sound

If the 1920's were the Jazz Era, the 1930's the Swing Era. Jazz became more orchestral, with the addition of stringed instruments. Swing, with its swinging danceable beat, kept the percussive rhythms of the African heritage, along with the call-and-response concept of alternating melodic statement of a theme with solo riffs and variations, sometimes keeping only the chord structure of the original melody. They also introduced new instruments, such as the saxophone, an instrument scorned by classical musicians. Jazz also incorporated the use of glissandos and glides, often featuring "blue notes," or the "notes between the notes," often flatted thirds, fifths, and sevenths, and sometimes microtonal notes that were not part of the usual well-tempered scale. (Percy Grainger would later relate these microtones to his concept of Free Music.)

As Blacks migrated north to various northern cities out of the Deep South during the Great Migration, different styles of jazz developed, such as St. Louis Jazz, Kansas City Jazz, and Chicago Jazz. Many Black musicians from New Orleans, including Louis Armstrong and his mentor, "King" Oliver, who had played in Storyville, went to Chicago. Some popular band leaders were Black, like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington, but many were white, like Paul Whiteman, styled the "King of Jazz" and Benny Goodman, the "King of Swing," who led one of the first integrated jazz groups.

Modern developments

In the era following the years we are discussing, the jazz heritage has influenced many forms of popular music, including soul, disco, and rock and roll, moving ever farther from its origins. Interestingly, Black musical forms have arisen that return to the rebellious roots of those original chants, namely rap and the associated hiphop culture. These compositions, like their forbears, depend not on melody but on a rhythmic patter and on trenchant commentary on events in the life of the singer and his audience. First associated with gangs in the form of "gangsta rap," these compositions also grew out of "the dozens," a game in which contestants try to outdo each other in trading insults, often involving the contestants' mothers. These could take the form of rhyming verses or single lines. (Example: "Yo momma so stupid it takes her an hour to cook Minute Rice".) Boxer Muhammad Ali frequently used such playful versified insults when speaking to reporters, simply leaving them confused. Rap, like jazz before it, has also been taken up by white musicians, with performers like white rapper Eminem, and has gone mainstream, as with popular female rapper Cardi B. Rap has also traveled abroad, to countries like South Korea, where it appears as K Pop.