Bernard Herrmann as he appeared in the Hitchcock motion picture classic “The Man Who Knew Too Much”

By Dana Paul Perna. It will come as no surprise to this readership that Bernard Herrmann is included amidst a shared appreciation among Grainger enthusiasts. The person to whom he was said to have once stated “Grainger changed my life” (quoted as per John Bird to me in a personal conversation), as well as “Grainger was my only true teacher”, how could he not rank high among those who could tout having been artistically nurtured by the Thunda-from-Down-Unda? Among the recordings Herrmann had planned to make had his sudden death not intervened, was one to have been devoted to Grainger in all his tuneful percussion richness and imagination. It came to pass in the hands of another conductor, but one only wishes we could have heard Herrmann bring his own original concepts and vision to the endeavor, especially if it were to have become one of his London Phase 4 discs, whereby all of it would have been captured on tape by way of that legendary audio engineer extraordinaire, Arthur Lilley.

Without any ego attached to any of what I am about to author, in 1986, I wrote an article about - and titled - BERNARD HERRMANN - for the Grainger Society Journal, as linked here for your reading pleasure and enjoyment. Greatest examples of the Journalistic Arts? Hardly, but my intention was related in a similar mode to those of my same intentions with regard to Grainger. During this period, in a pre-YouTube, Spotfly, TCM, Social Media, TicToc - what have you - World that it was, when I were to mention Herrmann, or Grainger, or Moross even to “intelligent musicians” - and, may I add, pianists, specifically with regard to Grainger - they would look at me as if I had four eyeballs - or any other BALLS (which it took, believe me) to express such well-warranted admiration with respect to either of them. Pianists, as I was to discover, were particularly clueless in terms of Grainger’s output for their instrument. Like Percy, there was almost nothing in relation to there being any presence of Herrmann, even during his 75th birthday year that 1986 marked. It was my feeling that Percy would not have minded having devoted space within a journal he was named for to expose a spotlight on one among his more - if not the MOST - illustrious of students.

It was Grainger who encouraged the young musician, as Jerome Moross shared with me while expressing his similar reaction to Grainger as his informal teacher. (Moross was not “enrolled” in Percy’s NYU class - Benny, however, was.) As Moross reflected: “To Grainger, there were two kinds of people; those who were interested in Music, and those who were not. If you were ‘not’, he had no interest in you. If you “did”, like Benny and I, class began after ‘class’ had ended.” Who else but Grainger would, not only talk about Early Music in depth and specificity - at a time when that was almost unheard of - but, actually bring in to class recorders, shawms, and even a serpent, in addition to playing these instruments as demonstration to the class, sometimes with his wife Ella in tow, while dressed in whatever was left of his World War I doughboy uniform, as Moross stated, “looking more like a Hobo than the other formally attired professors we were accustomed to.” (It should be noted that Herrmann later employed a Serpent to underscore a tarantula for his score to the motion picture “White Witch Doctor.”) He also expressed his admiration for Grainger’s effusive approach to music, his expansive knowledge of the subject, and his unorthodox approach to teaching it that allowed Herrmann, Moross and others, to look at music in a more open-minded manner. (It remains to be noted that Herrmann’s other teacher at NYU was Philip James, who, among other things was the first music director of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra that he co-founded in 1922.)

In terms of the “after class” Moross mentioned, as he continued, “No music subject was off limits! He never treated us like ‘youngsters’; he always treated us like equals - just young ones. Benny was like a sponge then” adding that Grainger was especially pleased that Herrmann was so deeply interested in, enthralled and inspired by the British composers, several of whom Percy knew, or had known personally. Particular attention must be paid to their mutual admiration for Frederick Delius, stories about whom Grainger imparted to his younger colleagues. It is no wonder why some of Herrmann’s earliest efforts reflect and possess a certain “Delian Aura” about them, such as his early concert masterpiece “Aubade”, the title to which he later changed to “Silent Noon” after the Rossetti poem of the same name: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fCAK_FogZS0 ….and, yes, Herrmann was present when Grainger invited Duke Ellington to visit the NYU campus, calling Moross to “GET YOUR ASS DOWN HERE IMMEDIATELY!” since he did not want his DeWitt Clinton High School classmate to miss out on such a history-making event.

Herrmann came to know the who’s who among his contemporaries, largely due to his participation in the Young Composer’s Group, but on his desire to do so as well. Among those whom he came to know during this early period included Copland, Siegmeister, Gould, George Gershwin, Robert Russell Bennett, Oscar Levant, Brandt, Ives, Cowell (who served as his first publisher), Still, Varèse, Vernon Duke, Charles Seeger among numerous others. Grainger participated (performing “Green Bushes”) on Herrmann’s first concert of the New Chamber Orchestra of New York on May 17, 1933, an orchestra that Herrmann formed at age twenty-one! - during the Great Depression when no one had $$$$$. How crazy is that? You can read a letter Benny wrote to Henry Cowell (a musician also associated with Grainger) the day after the concert by going to: http://www.bernardherrmann.org/articles/a-letter-to-henry-cowell/ By the time he assumed a staff conductor’s position for the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) in 1934, confidence would never be a characteristic Herrmann would ever be accused of NOT possessing. Two years later, he was appointed music director of their Columbia Symphony Orchestra, forging a name for himself within the medium of Radio, pre-dating his future work in motion pictures, television and recordings.

To state that “the rest is history” would prove an understatement.

Turning back to my previous 1986 article, what has changed since? When there were only a handful of recordings of Herrmann’s concert and chamber works on the market, including one devoted to his opera “Wuthering Heights”, these were mainly the products of Herrmann himself, either as performed under his baton, or under his supervision. Even these had become hard to come by. When YouTube began, Herrmann was not particularly present, nor was Grainger, for that matter, either. Over time, what has changed (as it has for Grainger), in a huge way is that Herrmann is very much present now. Early in TCM’s broadcasting of films that he scored, for example, mention of his contribution to their end result, unless it was one of his Hitchcock gems, was never included, which is not the case any longer. That his concert titles have been taken up in contemporary times, including the fact that his “Symphony” was finally given a long-overdue performance in Carnegie Hall (e.g. as performed by The Orchestra Now, conducted by Leon Botstein that occurred on Friday, November 3, 2017 at 7:30 pm in Stern Auditorium/Perelman Stage), has proven that those of us who knew of this Master’s hand would find-an-audience became confirmed. New recordings have been produced, and YouTube is bursting with Herrmannism to the extreme….and that’s just for starters. Even a selection of his “sketches” have been converted, in several instances, by way of digital representation over that medium, one that had not existed during Benny’s lifetime. There is even the online Bernard Herrmann Society website that established the Maestro with a Social Media presence he could never have imagined. Check it out for yourself by going to: http://www.bernardherrmann.org/ .

Orchestras that once openly looked “down” on his music are programming it - and what a list that is becoming, too. Los Angeles Philharmonic - an orchestra Herrmann was “forbidden” to conduct nor to perform his music - released one commercially made CD devoted to Herrmann’s film music under Esa-Pekka Salonen’s direction, while they have performed some of his titles in concert since; in fact, during the inaugural week of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, selections by him were included among those historic festivities, and eventual telecast.

The New York Philharmonic performed Herrmann under the baton of no less than John Williams, who had also programmed Benny’s work years earlier while he was music director of the Boston Pops. Of course, Herrmann is part of their history, having received the world premiere of his “Moby Dick” under the baton of then music director, (pre-Sir) John Barbirolli.

The New York Philharmonic performed Herrmann under the baton of no less than John Williams, who had also programmed Benny’s work years earlier while he was music director of the Boston Pops. Of course, Herrmann is part of their history, having received the world premiere of his “Moby Dick” under the baton of then music director, (pre-Sir) John Barbirolli.

photo of Bernard Herrmann discussing his score to MOBY DICK with conductor, John Barbirolli, then music director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra

More recently, the New York Philharmonic’s string section (with mutes!) performed Herrmann’s score for “Psycho” in a “live” performance while the Hitchcock classic was being screened. His “Psycho Suite”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fQwzJ6VvUD0 (released under the title “Psycho (a Narrative for Orchestra)” on Benny’s recording: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBkuUc6Pvek) has practically become a concert staple for Halloween, or “Thriller”-themed concerts. In Bordeaux, France, a great deal of attention was paid to Herrmann over three events in which HE was the featured subject. The first concert’s audio was cybercast, meaning that I was able to listen to it while it happened - this truly supreme presentation: Thursday 7th and Friday 8th of March 2019 at 20hr – Concert “Bernard Herrmann – The Golden Age of Hollywood Cinema”. The Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine (ONBA) conducted by David Charles Abell, and with soprano Ana Maria Labin and the pianist Tanguy de Williencourt, will offer a program that will include music from the movies Psycho, Fahrenheit 451, Citizen Kane, The Bride Wore Black, Hangover Square, Obsession, The Ghost and Mrs Muir and North by Northwest. Yet, two more events occurred during the same week, these: 1) Monday 11th of March at 20h – Music Conference “Bernard Herrmann – His life and his great scores” Thierry Jousse, film critic and French director, will speak about the life of Bernard Hermann and his great scores written for the cinema, accompanied by Jean-Michel Bernard, pianist and composer, who will musically illustrate this tribute to the great Maestro; 2) Thursday 14th & Friday 15th at 20h – Movie in concert “Vertigo” The Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine (ONBA) conducted by Ernst Van Tiel will perform live Bernard Hermann’s soundtrack for the movie “Vertigo” (1958), directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

…and that does not even scratch the surface in any way, shape, or form! In terms of his work just for the cinema alone - excluding everything else, which is quite an “else” to exclude!!! - he has become one of the most revered, studied and influential figures to have ever graced the medium. For that reason, he can now be considered to rank among the most important composers to ever have been born on the soil of the United States of America, period.

To fail on my own side of the coin would prove inexcusable, therefore, I prepared two episodes of my cyber-radio program devoted to Herrmann’s work, the first providing an overview of his life and career: http://mixlr.com/moog1-radio/showreel/dpp-17/ It additionally pleases me to inform readers that, years ago, I had the great privilege of “crashing” the concert and first recording session in Phoenix, Arizona devoted to Herrmann’s previously alluded to “Symphony.” (While Herrmann had recorded it, it had not been recorded in a digital form of a later vintage.) One of my fondest memories was when the trumpet player entered the sound room to check in. His T-Shirt read “I Think Before I Clam.” How reassuring!?!?!? To myself, I immediately thought, what WOULD Benny have exclaimed if he had seen that? True, he could have laughed out-loud, but, more likely, given how serious he was when it came to all matters where and when WORK was involved, I could well imagine him having yelled out:

“HEY, THAT’S DISRESPECTFUL! EITHER TAKE THAT SHIRT OFF, OR GET THE HELL OUT!”

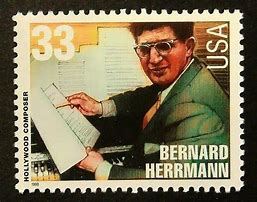

Oh, yes, and let’s not forget that Benny has even served as postage:

To our great fortune, Herrmann’s contributions carry on in the 21st Century, perhaps even more musically relevant than ever. I have even heard a small combo jazz quartet - YES, a JAZZ QUARTET !!! - play his theme to “Taxi Driver” in a manner that the other standards were handled on the same gig. Too HIP for the room? You better believe it, Daddy-O. In a different version by a different artist, just to show you what I mean, DIGGETH - as BENNY’s tune ROCKS THE HOUSE ANEW! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSMmuejLMFI Absolutely 100% delicious - just as if Travis had stopped the meter long enough to dig into a New York Pastrami-on-Rye from Katz’s!

In the end, what else can be learned by any of this? Whether it was Grainger, or Herrmann, or Moross, or Germaine Tailleferre, or Cyril Scott….. or any among a number of composers one feels has been neglected, vindication - not just that it comes, but when it comes - is always such a wonderful thing, indeed!!!!

In the end, what else can be learned by any of this? Whether it was Grainger, or Herrmann, or Moross, or Germaine Tailleferre, or Cyril Scott….. or any among a number of composers one feels has been neglected, vindication - not just that it comes, but when it comes - is always such a wonderful thing, indeed!!!!

Postscript

Upon completing this article, some additional news came my way, thereby making the necessity for this much-needed POSTSCRIPT. A bit macabre though it may be, yet remembering that Bernard Herrmann did compose a “Concerto Macabre” (for piano and orchestra), this latest addition, therefore, will seem wholly appropriate as you read on.

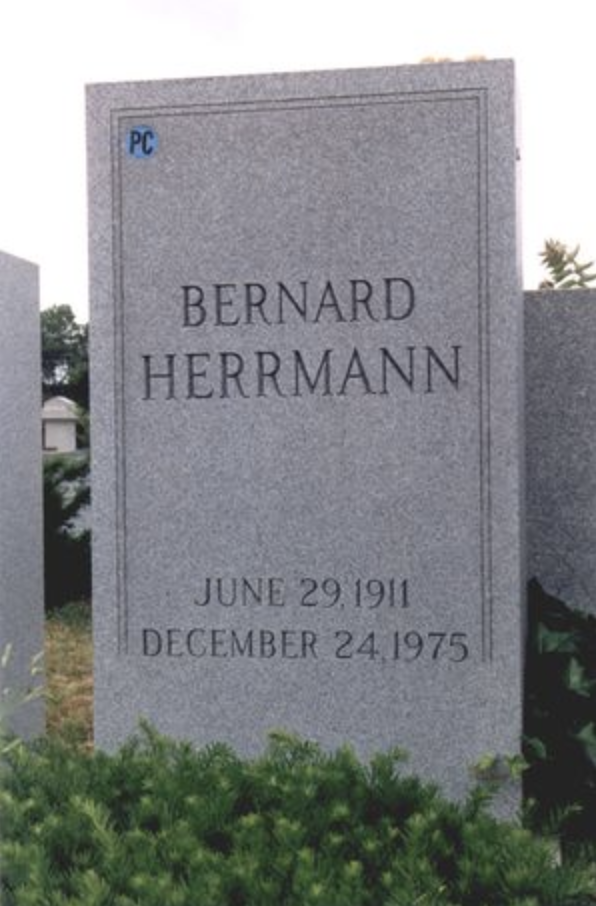

Upon learning that Herrmann was buried some 25 minutes from where I lived, I decided that it was only fitting for me to pay my respects by visiting his grave, which I did on two attempts. The first attempt became a wash-out, while attempt number two, fortunately aided by a groundskeeper, could not have gone any better. The weather was perfect - sunny and bright, not too warm, the air was crisp, the location appropriately quiet, if not a bit eerie, too (e.g. no one was there other than the groundskeeper [who walked away] and me). At left, how the site appeared at that time.

Upon learning that Herrmann was buried some 25 minutes from where I lived, I decided that it was only fitting for me to pay my respects by visiting his grave, which I did on two attempts. The first attempt became a wash-out, while attempt number two, fortunately aided by a groundskeeper, could not have gone any better. The weather was perfect - sunny and bright, not too warm, the air was crisp, the location appropriately quiet, if not a bit eerie, too (e.g. no one was there other than the groundskeeper [who walked away] and me). At left, how the site appeared at that time.

I know what you are thinking, but, yes, as truly simple and direct as a demarkation could get. You would never suspect that this is the resting place for one of the Masters given its understatement. (The dot at the top left indicates that this site is to be “perpetually cared-for”, which forms, in part, the basis for this “postscript.”) In paying my respects, I included mention of Percy Grainger, Henry Cowell, Charles Ives, Jerome Moross, and Edgard Varèse within my salutation (why not?), plus all the members of any-and-all the Percy Grainger Societies, John Bird, Barry Peter Ould, William Grant Still and Kevin Scott….before adding my final gesture; the reason for this pilgrimage in the first place.

Some of you will know that Herrmann’s first wife was the renowned writer, Lucille Fletcher, among whose most famous works remains “Sorry, Wrong Number” having aired as a chilling radio drama in 1943 that starred Agnes Moorehead, later having been turned into the motion picture classic that starred Barbara Stanwyck and Burt Lancaster (the latter having been a classmate of Herrmann’s [and Jerome Moross, too] at DeWitt Clinton High School in New York.) Just to add this tiny touch of color onto the fabric, Ms. Fletcher’s drama formed the basis for the final stage work Jerome Moross (Benny’s classmate and childhood friend) was to complete. He was at work on it - its manuscript sitting in its working stages on his piano - when I visited Moross at his New York apartment. At right, poster for the Motion Picture release of "SORRY, WRONG NUMBER"; the cinematic adaption of Lucille Fletcher's historic radio drama.

Some of you will know that Herrmann’s first wife was the renowned writer, Lucille Fletcher, among whose most famous works remains “Sorry, Wrong Number” having aired as a chilling radio drama in 1943 that starred Agnes Moorehead, later having been turned into the motion picture classic that starred Barbara Stanwyck and Burt Lancaster (the latter having been a classmate of Herrmann’s [and Jerome Moross, too] at DeWitt Clinton High School in New York.) Just to add this tiny touch of color onto the fabric, Ms. Fletcher’s drama formed the basis for the final stage work Jerome Moross (Benny’s classmate and childhood friend) was to complete. He was at work on it - its manuscript sitting in its working stages on his piano - when I visited Moross at his New York apartment. At right, poster for the Motion Picture release of "SORRY, WRONG NUMBER"; the cinematic adaption of Lucille Fletcher's historic radio drama.

Upon their marriage, the couple spent their Honeymoon at the Grand Canyon. As part of my visit to that same Natural Wonder, I picked up a piece of Arizona red rock, both as a souvenir, and as a just-in-case I were to ever visit Herrmann’s resting place (that’s truth, by the way!!!) The time had come with regard to that well intended visitation as I placed, as is customary, this most appropriate chunk of Arizona red rock on the top right of his gravestone. Two other stones (of a more local variety) had already been placed there making me realize that Benny had not been forgotten. This company of stones looked somehow very cozy together as the luminescent sunlight fully illuminated them. Having occurred on a late Tuesday morning, with my pilgrimage thus completed, I went to lunch at Rachel’s Café in Syosset before returning home.

While preparing this article, I planned to locate photos to enhance some of my verbiage with pictures. Among them included Benny’s resting place. Not that I was planning to use any of them, I noticed that, when I had paid-my-respects, it was just his stone and a shroud created out of a low-resting bush - exactly like all the others in the row. Since that time, it would appear that his family has stepped in, having added an additional stone at the foot of it.

While preparing this article, I planned to locate photos to enhance some of my verbiage with pictures. Among them included Benny’s resting place. Not that I was planning to use any of them, I noticed that, when I had paid-my-respects, it was just his stone and a shroud created out of a low-resting bush - exactly like all the others in the row. Since that time, it would appear that his family has stepped in, having added an additional stone at the foot of it.

You can almost consider it to be a “coda”; an appropriate form of expression with which to pay homage to one of the most remarkable figures Music has ever known.  Bernard Herrmann's gravesite as it appears now

Bernard Herrmann's gravesite as it appears now